RECONSIDERING THE ANONYMITY OF THE GOSPELS.

A Brief Textual and Historico-comparative defense of the gospel’s authorship.

Introduction

Since Hermann Reimarus in the 18th century till our contemporary period, Scholarship on the historicity of Jesus is heavy laden with variegated criticism towards the primary source for his life; the gospels. Of all the criticisms, the one that seems to stand out is the generally accepted view of the gospel’s anonymity. It has been a much prevalent topic in new testament scholarship but it had more or less, remained within the confines of biblical criticism since the debate arose. Quite a number of scholars like Mitchell Reddish in his An Introduction to the Gospels, have argued that the gospels weren't written by eyewitnesses nor broadly speaking, their attributed authors. Even prominent evangelical scholar, Craig Blomberg has once admitted that "it's important to acknowledge that strictly speaking, the gospels are anonymous."[1] However, the view now enjoys wide acceptance, particularly outside biblical scholarship. A specific scholar to thank for its popularization would be one of the top New Testament scholars and New York times best-selling author, Bart Ehrman.

If the anonymity thesis is true, the effect then is that, with the exception of Christian apologetics circles or Christians generally, there's a “scholarly” consensus that the canonical gospels are anonymous. Furthermore, the term "anonymity" would simply be an euphemism for pseudonimity and the inescapable conclusion would be that early church fathers, who allegedly affixed this names, intentionally and falsely attributed the gospels to these authors.

Th intent of this article, drawing from new testament scholarship (especially areas that have been overlooked), is to revisit these postulations, argue otherwise and establish that, contrary to popular opinion, there's actually a substantial amount of evidence that provides a very strong basis for the original superscriptions of the gospels. Though I admit the apologetic undercurrents to this work, i have nonetheless spent a significant amount of time critically analyzing the sources used in writing this article, often discarding popular level arguments that a lot of Christians find convincing which, on the other hand, i don't believe withstands proper scrutiny.

As observed by Peter Stulmacher, in biblical scholarship, the presuppositions of the gospel’s investigator often dictates the historical trajectory more than one might suppose and he also noted that apriorism has been a characteristic feature in biblical criticism. [2] Given this factor i tried as much as best as I could to subvert my bias and be as intellectually honest as i could. However, while i think the statement accrues to both conservative and liberal scholars, i couldn't help but think this applies especially to skeptical scholars who analyze the bible through the lens of methodological assumptions. For one thing, after I evaluated the grounds from skeptical scholarship (particularly Bart Ehrman) for the gospel's anonymity, i surprisingly found most to be non-evidenced assumptions. Though arguments have been written by new testament scholars in favor of the traditional ascriptions of the gospels, but given that other aspects of the gospels are being covered, details are usually condensed into a short chapter. Therefore, this article is an attempt to briefly expand on the topic from comparative-historical and textual perspective.

The gospels were composed in antiquity, a period where nearly all the classical works that have shaped our societies. Some of these works circulated anonymously, yet people were well aware of the authors. Given this fact, if there might be parallels between the gospels and some literary genres, then one can firmly infer that the [literary] reasons for which the gospels are deemed anonymous are non-sequitur. I also try ascertain that a textual study of Luke makes it highly plausible that Luke was written by its attributed author. lastly, i attempt to demonstrate that the canonical gospels strongly reflect the the socio-cultural milieu of first century Palestine especially with the kind of names they bore, something we don't comparatively detect in the apocryphal gospels.

The lacuna of this article is that my thesis is generalistic, as such, i don't spend enough time on each gospel except Luke and even at that, briefly. This article isn't exhaustive and is only meant to laud a changed perspective and an unbiased approach concerning the authorship of the gospels.

The Anonymity Thesis

"The books are thoroughly, ineluctably, and invariably anonymous. At the same time later Christians had good reasons to assign the books to people who had not written them."

-Bart Ehrman [3]

Generally, most scholars, whether from informed evaluation or mere speculation, hold that the gospels are anonymous and to argue otherwise is to attract the indictment of fundamentalism.

Rebecca Denova, American historian who focuses on the history of early Christianity, stated in her entry for world history encyclopedia that,

in their attempts to provide background for the writers, the church fathers tried to align them as close to the original circle of Jesus as possible. they were also aware of fundamental problem; the first disciples of Jesus were fisherman for galilee who could not read and write the level of Greek in these documents.

out of curiosity, i assessed the bibliography of the article and the first on the list was....Bart Ehrman.[4]

Likewise, History channel assertively notes that

All four Gospels were published anonymously, but historians believe that the books were given the name of Jesus’ disciples to provide direct links to Jesus to lend them greater authority. [5]

In another article written by History Channel, Ehrman was also in the bibliography. It was earlier stated that Ehrman’s scholarship seemed to have aided in the popularization of the anonymity thesis, and given this, his opinions on the gospels informs what many come to believe about the gospels, it's necessary to unpack what exactly Ehrman's argues.

Ehrman begins by pointing out that illiteracy was widespread in the roman empire and the only ones that were literate were the upper class which only made up about 10% of the populace. drawing from Acts 4:13, he further argues that the disciples were lower class peasants from rural Galilee, which by implication, made them functionally illiterate. Given that Jesus’ followers were lower-class peasants who spoke only Aramaic and not Greek, it becomes highly unlikely, therefore, that these disciples played a role in the literary composition of the canonical gospels, documents which seem to have been published outside composed outside Palestine.[6]

How then did these names find their way as superscriptions on the gospels? Ehrman (amongst others) offers that Sometime in the second century, the proto-orthodox church finally saw the need to attribute the gospels to either the disciples or companion of the apostles, when in actuality, the gospels were written by well-educated Greek speaking Christians in the mid-second century [7] Otherwise, the gospels themselves do not as much as offer any concrete information about the identity of their authors and we only identify the gospels with their alleged authors because of the added superscriptions in the middle of the second century. [8]

Also, Ehrman thinks the current form of the gospels are likely divergent from things that actually happened and the words that Jesus actually said. Since first-century Palestine was an oral society, granted the level of illiteracy, the sayings now encapsulated in the gospels were told for decades by people who had heard them 5th-hand, 6th-hand or even 19th-hand before the decision to have them written down. [9] Therefore, due to the gospels being written in different countries, different contexts and a different language, [10] they preserve traditions that have been retold and modified overtime such that we cannot possibly rely on them to show us what the eyewitnesses originally claimed about Jesus, much less their identity. [11] “Thus, the New Testament documents were written anonymously.” [12] In this article he also briefly offers why he thinks Matthew couldn't have have been the author of the gospel attributed to him.

Recently, i incidentally came across a video from a YouTube channel: Mythvisionpodcast, where the slightly affronting image was displayed on my screen.[13]

I had two impressions; The first [and stronger] one was that it was a clickbait i was going to hear another scholar with a PhD tell me the what i have read from skeptical sources already. Then again, i second-guessed it by wondering if there really was something about the gospels that was otherwise obscured. Either way, it's needless to say i would prove my prior assertion true.

The Scholar was Robyn faith Walsh, an associate professor at the university of Miami, where she teaches on early Christianity and ancient Judaism. Through the podcast, she summarized her monograph The origins of early Christian literature and after listening for a considerable amount of time, her presentations were indistinguishable from Ehrman’s position on the gospel’s origins. After she makes a cumulative case why she thinks the gospels weren't written by their attributed authors, she supplied,

We don’t know a lot about early Christianity, we don’t know a lot about the origins of this movement, we know mostly about Paul…we don’t even know who wrote these gospel. These attributions…these names are later [additions], just so people wouldn’t confuse the manuscripts….it’s all shrouded in a lot of mystery.[14]

It's no surprise then, that every skeptic i have interacted with about the gospels, believe they were written anonymously, even worse, a few have even claimed that the gospels were written 100 years removed from the events! Before I argue my case, I’d first like to situate the narrative within the time period where the eyewitnesses were alive to have offered Oral History and Oral tradition in the process of the gospel’s composition.

Gospel Dating and Eyewitnesses: a papyrus from fayyum

The dating among scholars for the gospels vary with some favoring and earlier dating while others a later dating. Either way, the mainstream consensus is that the gospels were written between 70A.D and 100 A.D. This part of the article would ordinarily be needless except to address skeptics who have a habit of situating the gospels at a much later period. for instance Dustin Jones, who blogs about biblical studies and early Christianity cites Justin Matyr, who was quoting the gospels at about 155A.D and claims Matyr doesn't address any of the gospels writers by name but simply refers to the gospels as "memoirs." He then concludes that,

From this data, we can conclude that the gospels must have been written sometime between 30CE and 150CE [15]

This position is correct, however, we nonetheless get the strong impression from Justin Matyr in his Dialogue with Trypho where he indicates that the gospels weren’t just composed by the apostles (which if true, indicates John and Matthew) but also by their direct followers ( in this case, Mark and Luke being followers of Peter and Paul respectively). Quoting Luke, he writes

For in the memoirs which I say were drawn up by His apostles and those who followed them, [it is recorded] that His sweat fell down like drops of blood while He was praying, and saying, ‘If it be possible, let this cup pass: [17]

Nevertheless, Jones leaves room for the removal of composition of the gospel's proximity to the eyewitnesses and the lands where they are purportedly narrating the events. Little wonder uninformed skeptics often state something that sounds like " The gospels were composed 100 years after the events and couldn't have been eyewitnesses accounts.” Hence, my purpose in talking about gospel's dating here is twofold:

1) To firmly situate the narrative within the late first century, where the ascribed authors, (if indeed they truly are) were situated.

2) Progress, with the rest of the article based the educated assumption that the gospel authors and some of the eyewitnesses of Jesus ministry were alive must have been alive at the point of Mark and Matthew were written, which were composed earlier than Luke and John.

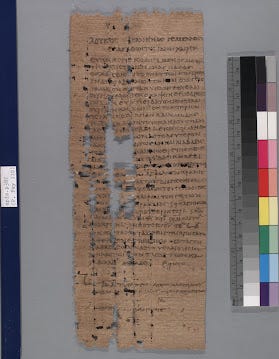

There are no extant autograph manuscripts of the gospels, but there are numerous Greek copies and the earliest are designated P90, P66, P4, P64 and P67 (Magdalen papyrus), P75 and P104 all of which date between the mid second century A.D - late second century A.D. the area of interest is on the discovery of the "John Rylands Papyrus 457" or simply Papyrus 52, better yet, P52. [16] Though there’s no general consensus amongst scholars as to the dating with dating ranging from 117-135 A.D and some as late as 125-175 A.D (which is highly implausible as I try to show shortly).[17]

A way through which paleographers date papyri is by ascertaining the writing styles of the documents being analyzed. If the analysis shows the writing style to be in consonance with a particular period where that particular writing style thrived, the date would be situated within that period. This is why P52 is significant, because apart from the fact that its writing styles bear distinctive marks that separate it from other early New Testament documents, it’s early dating can inferentially establish the gospels were written much earlier in the first century, when the eyewitnesses were still alive.

As earlier mentioned, the significance is that P52 bears strong similarities with other ancient document, most of which belong to the reign of Hadrian (r. 117- 138 A.D) in the early 2nd century, but its most striking similarity is with Papyrus Fayyum 110, a document discovered in 1898–99 by B.P. Grenfell and A.S. Hunt in the Fayum village of Kasr el Banât, ancient Euhemeria [18] The document entails a letter written by Lucius Gemellus to his slave, Epagathos regarding their olive orchard. The point of interest in this papyrus isn’t the content but rather that Gemellus, fortunately dates the papyrus to be during the "fourteenth year of the reign of emperor Domitian" which invariably is A.D 94, the ending decade of the first century.[19]

Timothy Jones, New Testament scholar, surmises that if John was the last gospel to be written, and there were already copies circulating around the Roman empire (since this fragment was discovered in Egypt) in the early 2nd century, this places the composition of the original manuscript [and the earlier gospels, by extension] sometime in the late 1st century where the witnesses of the events they recount would still be alive. C. H Roberts, one of the scholars who analyzed the papyrus, also seems to posit a similar view point.[20] Notable German Philologist, Adolf Deissman has also expressed the line of thought that this places the composition of John's gospel at the late first century. [21]

Incidentally, we find Quadratus of Athens, a bishop and apologist of the early second century, inadvertently substantiating this claim, when he wrote a defense of the Christian faith to Emperor Hadrian after some “wicked men” had troubled some Christians, [22]

The deeds of our Savior, were always before you, for they were true miracles; those that were healed, those that were raised from the dead, who were seen, not only when healed and when raised, but were always present.. They remained living a long time, not only whilst our Lord was on earth, but likewise when he had left the earth. So that some of them have also lived to our own times.

Quadratus to Emperor Hadrian [23]

A.D 33, when Jesus was crucified, to the time where Quadratus was writing seems like a stretch and would be obvious to even Quadratus and the people he was writing to. So he must of have been talking about an earlier period in his own lifetime.

Having structured the line of argument to strongly accommodate the stance that these gospels were written in the late first century, where their attributed writers are purportedly alive, the next line of inquiry would be see if there early testimonies that attribute these gospels to their alleged authors.

Normally, i wouldn't have to include these testimonies in writing this article, because i presumed some would be familiar with them and to state them here would simply be repetitive, but a reconsideration made me realize this presumption excludes people who aren't conversant with the topic of anonymity. Also, i believe the multiple testimonies would be seen in a fresh and veritable perspective after i make three cases in defense of the gospel's authorship. Lastly, though we have several testimonies that attest to the traditional authorship of the gospels, for the sake of time and an aversion of being monotonous, i would only quote the earliest ones.

The earliest attestation we have comes from Papias of Hierapolis, an early Christian figure who was a "hearer of John [the apostle] and companion of Polycarp" and also knew Philip's daughters, who in turn knew the apostles. Papias narrates from a tradition he received probably around the late first century and was written in the early second century,

i wont hesitate to to arrange alongside my interpretations whatever things i learned and remembered well from the elders, confirming the truth on their behalf....the elder said this: Mark, who became peter's interpreter, wrote accurately as much as he remembered though not in ordered form, of the lord's sayings and doings. For [mark] neither heard the lord not followed him, but later(as i said) he followed after peter, who was giving his teachings in short anecdotes and thus did not bring forth an ordered arrangement of the lord's sayings; so mark did not miss the point when he wrote in this way, as he remembered. for he had one purpose. to omit nothing of what he had heard and to present no false testimony in these matters...And Matthew, in the Hebrew dialect, placed the sayings in orderly arrangement.

-Papias of Hierapolis (c. 60- 130 A.D) [24]

Though this testimony is the earliest, There are no extant works of Papias and his fragment is quoted by church historian, Eusebius in the 4th century. This is not an issue though, because a great deal of historically established facts or individuals have come from quoted works that haven't survived. Take Socrates for instance, one of the most easily recognizable names in Classical Greek philosophy; yet all that we know about Socrates comes mostly from Plato and with other parts coming from Xenophon yet almost no one questions Socrates' historicity.

The second issue a good observer might take up is that all the earliest manuscripts we have about the gospels were all written in Greek, yet we have Papias claiming Matthew composed his gospel in Aramaic.

Be that as it may, there's a good chance, Matthew initially wrote his gospel in Aramaic but would later translate it to Greek; one speculate this because within the first 30 years of Christianity's inception, the gentiles more than Jews showed special interest as the gospels spread viz-a-viz the establishment of Christian missions in Syria, Asia Minor, Greece, and Italy, places where Greek was mostly spoken [25] For example, the fact that Greek was also spoken widely necessitated Josephus who composed his Jewish war originally in Aramaic to eventually eventually translate it to Greek so it could reach a larger audience [26] Though there are Scholarly debates as to the reliability of Papias, there hasn't been any tenable evidence to doubt this attestation.

The next early testimony comes from Polycarp of Smyrna, a Greek bishop in Asia minor, reputed to be one of the disciples of John, according to church tradition. Polycarp notes,

Matthew also composed his gospel among the Hebrews in their language , while peter and Paul were preaching the gospel in Rome and building the church there. after their deaths, Mark peter's follower and interpreter handed down to us peter proclamation in written form. Luke, the companion of Paul, wrote in a book the gospel proclaimed by Paul. finally, john the lord's follower, the one who leaned against his very chest composed the gospel while living in Ephesus, in Asia.

- Polycarp (c. 69- 155 A.D) [27]

We can trust Polycarp's testimony because he was within the circle of the apostle's disciples and would have been familiar with the composers of the new testament gospels. To corroborate this claim, We find Irenaeus in his letter, a description of Polycarp's interaction with John,

i can still describe the very spot in which the blessed Polycarp sat as he taught; i can still describe how he exited and entered , his habits of life, his expressions, his teachings amongst the people, and the account that he gave of his interaction with john and with others who had seen the lord. as he remembered their words and what he has heard from them about the lord and about his miracles and teachings, having received them from the eyewitness of the "word of life" Polycarp related all of it in harmony with the scriptures....continually, i can still recall them in faith. - Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 130- 200 A.D) [28]

Under normal circumstances, this would have provided support, in the discipline of history; however, an unfair amount of doubt has been casted on these writings and most have been premised on non-evidenced assumptions. As noted earlier, it's been postulated that the early church simply ascribed these names to grant them canonical authority.

This is, of course, misleading as many conservative scholars have rightly argued that if the authorship of the canonical gospels were falsely attributed to grant them authorial credence, the four authors seem like highly unlikely candidates for such conspiracy. The apocryphal gospels like the gospel of Thomas, Peter, Judas, Mary, Philip, Apocryphon of James and Apocryphon of John all claim to narrate eyewitness accounts of Jesus, and attribute their gospels strictly to popular eyewitnesses (i will analyze later on what the gospels portray as credible accounts, that the apocrypha don't ).

In contrast we don't experience that with the gospels. Firstly, Mark and Luke are anything but eyewitnesses; they were companions of the apostles. Given the proclivity of the apocrypha to ascribe authoritative names, it seems very unlikely that it was the same case with the gospels. Matthew on the other hand, though an eyewitness, was a tax collector, an occupation strongly depicted within the gospels as promoting moral bankruptcy[29] So far, that leaves us with only John.

On the speculation about church fathers ascribing names of companions to the gospels, Martin Hengel, German historian and renowned scholar of religion, rectifies that to conclude the canonical gospels were attributed their authors only in the mid-second century by the early church is completely anachronistic. He further clarifies that apart from the fact that the church didn't have a central authority during this period, the first local synod in church history was held by Bishops of Asia Minor in the late 2nd century and it was in relation to the the doctrine of Montanism.[30]

Again, Hengel argues that by the middle of the second century, the gospels had circulated through Antioch, Lyons, Carthage and Alexandria. If by this period, they had circulated anonymously all over the the Roman Empire there would doubtlessly have arisen a diversity of attribution, where different names would been given to the gospels; this was usually problem that had occurred in antiquity for works whose authors were unknown. [31] Unsurprisingly, This is the exact diversity of attribution that occurs with the epistle to the Hebrews, an anonymous work. Unlike the gospels that possess unanimous agreement in attribution across churches in the west and east, not with a single name but four names. With the inclusion of Eusebius’s observation of diverse attribution, The following early church figures attributed different names to the Hebrews,

• Eusebius: “It should not, however, be concealed that some have set aside the epistle to the Hebrews, saying it was disputed as not being one of St.Paul’s epistles…” [32]

• Pantaenus: “Paul”

•Tertullian: “Barnabas”

•Origen: “who wrote the epistle, Only God knows. Traditions reaching us claim it was either Clement, Bishop of Rome, or Luke….” [33]

So we see no less than four attributions: Clement, Paul, Barnabas and Luke, for the book of Hebrews which was likely written before the gospels. At best, one can surmise the author did indeed intend for himself to be anonymous. Not only do we see a complete uniformity for one of the gospels but all four. Practically speaking, this is a highly unlikely possibility.

Additionally, with the way the early church took a strong stance against pseudepigrapha, it's arguably unlikely they would resort to the same means to validate what they considered sacred scripture. For instance, The Muratorian canon rejects the forged letters of Paul to the Laodiceans and Alexandrians, Tertullian was responsible for defrocking a church elder for composing the acts of Paul and falsely attributing it to the apostle. Even Serapion, Bishop of Antioch, repudiated the authenticity of the gospel of peter after scrutinizing the gospel despite its popularity.

As far as illiteracy is concerned, it’s a bit of a strawman to claim the eyewitnesses were all illiterate and couldn’t have composed the gospels. For one thing, Luke and Mark weren't even disciples, thus they fall outside Ehrman's Acts 4:13 indictment. Although it would be arguing from silence, John could have used an amanuensis to compose his gospel. As for Matthew, much contrary to Ehrman's claims, there is evidence that corroborates Matthew's authorship for his gospel. There are tax receipts (MS140 and MS150) which were written in Greek and dates as far back as 140-89 B.C, which shows that Tax collectors were, as a matter of fact, literate. Also, judging from the fact that Matthew would host a "great banquet" for Jesus with other tax collectors in attendance, partly attests to Matthew's importance and by extension, literacy.[34]

MS140

MS150

CASE 1: Argument from Greco-Roman Biography

The compositional make-up of bible consists of laws, history, poems, psalms, epistles, genealogy e.t.c That means each book fits into a category of genre. In this part, i argue that the gospels fit into the literary genre of biographies; not just any biography but specifically Greco-Roman. and that the gospels employed one of its literary convention: Anonymity. Prima facie, this seems unlikely but biographies were quite popular in the age of antiquity and the pertinent question becomes: if first century writer of the gospels were writing about a first century figure, to a first century audience, it only makes sense to utilize a biography in carry in this out, a genre which was pretty popular during that time in antiquity.

Be that as it may, this is only a claim and claims don't solely help to establish that the gospels are Greco-Roman biographies. Several scholars like Richard Burridge,[35] Samuel Byrskog,[36] Richard Burridge,[37] Mike Licona,[38] (with endorsement from Christopher Pelling, a classicist) and Craig Keener [39]have argued in the affirmative. Even German classical Scholar, Friedrich Blass in his Philology of the Gospels notes that there are similarities between the gospels and both Greek and roman literary conventions, pointing put a notable similarity with Plutarch's Lives, a biography.[40]

One might likely counter that if the gospels were indeed biographies, how come they contain such scanty information about the life of Jesus? Well, Greco-Roman biographies are not to be classified as the same category of our modern biographies; which follows a sequential progression of the subject's life [41] rather, they are moral exhortations portraying examples of a life worthy of emulation just as we see in the gospels [42]

For example, the closest parallels between the gospels and Greco-Roman biographies are Arrian’s Epictetus, Xenophon’s Socrates and Philostratus’s Apollonius of Tyana. Like the gospels, the purpose for writing these biographies were primarily for Moral-religious reasons and as such didn’t depict the lives with rigorous accuracy expected of a modern historian. The purpose of writing biographies were simply the eulogization of the figure and their ideals. [43]

Richard Burridge, further sheds light on this path of inquiry when he shows four literary features of ancient biographies that are commensurate with the gospels

1) Opening feature: Title and prologue.

2) The subject: An individual with which the primary emphasis is placed and serves as the over-arching narrative of the biography.

3) Internal features: Birth, ancestry, deeds, virtues

4) External features: Anecdotes, sayings, speeches and dialogues [44]

Having fairly established that the gospels are pattern like Greco-Roman biographies, it was stated earlier that anonymity was a literary convention often used by Greco-Roman historians. Dustin jones, a skeptic and biblical studies enthusiast, whose article on the anonymity i find interesting, argues against this position. Citing Armin Baum, another classicist, he claims that,

Apart from the epistles, the new testament gospels are likewise divergent from numerous other Greco-Roman and Jewish works from antiquity in which the authors of of the texts identify themselves within the body of the text. ancient historians and biographers such as Herodotus, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Suetonius, Thucydides, and Jewish writer Flavius Josephus all named themselves as authors of their respective texts.[45]

Therefore, he concludes,

if the gospel writers wanted their identities known and unambiguously associated with the individual gospel accounts, they could have simply followed the conventional literary norms and provided that information within the body of the text found most typically in the prologue or salutation of ancient writings [46]

while this might appear true, the conclusion is a tad hasty; there are Greco-Roman works that were initially anonymous whist circulating and Simon Gathercole, a new testament scholar with experience in classical history, shows this. Gathercole classifying Greco-Roman works into 3 categories: treatise, history and biography shows several works of Greco-Roman history that circulated anonymously. [47]

Technical Treatise

Demetrius's formae epistolicae, Hero of alexandra's pneumatica I, Diogenes' letter to antigonus, and Galen's De Typis (though Diogenes' letter, like Luke's Gospel, had an epistolary introduction) [48]

History

Although we don’t often find this literary convention among Greek historians, we often see them employed by Roman historians; one can find major figures choosing to not include their names, including Sallust, Livy, Tacitus and Florus [49]

Biographies

Josephus’s Vita was written anonymously. Plutarch, well-known biographer, doesn’t mention of his name in his Parallel Lives. Of all the biographies of Lucian, only Passing of Peregrinus has his name inscribed, but only as an epistolary prescript (‘Lucian to Cronus, with best wishes’); “Otherwise, Alexander the False Prophet, The Toxaris and The biography of Demonax have no mentions of Lucian’s name in a preface.” Finally, Porphyry’s Life of Pythagoras does not mention his name. [50]

Given the sufficient amount of works that circulated without the names of the authors, Gathercole argues that there was some form of identification with which the audience would link the author with their work.

Even Ehrman admits that

It was a lot common to write a book anonymously in antiquity than it is today [51]

And that

An ancient author did not need to name himself. [52]

Based on this premise we’d now have to make a distinction between partial anonymity (Despite the exclusions of early superscriptions, the audience/church could still link the gospels to their authors) and absolute anonymity (that no one knew who wrote the gospels so the church had to attribute them to the disciples and their companions).

There's the claim that if at all the gospels were modelled after biographies, why do they write in third-person and not first-person?

As Bart Ehrman opposes,

The Gospels came to be included in the New Testament were all written anonymously; only at a later time were they called by the name of their reputed authors, Matthew, mark, Luke and John….None of them contain a first person narrative (“one day when Jesus and I went into Capernaum…”), or claims to be written by an eyewitness or companion of an eyewitness. [53]

Dustin Jones also adds his voice of scrutiny when he writes,

The Gospels are composed completely in the third-person omniscient voice, a hallmark of Greco-Roman literary novels – but not biographical or historical literature. Those details have to be factored into how we understand and examine these texts within their immediate socio-cultural environment….[54]

while these might appear to be concerns, they are not a strong basis for inferring anonymity, especially when one considers the stylistic device called Illeism, where a writer refers to oneself in a third-person narrative despite describing…one’s self; and contrary to both claims, we find Illeism being utilized in Greco-Roman history.

Xenophon, Prominent Greek historian and military leader in his notable work Anabasis, employed an Illeist narrative. For instance, he narrates here in Third-person when he writes,

But when Cheirisophus saw that this ridge was occupied, he summoned Xenophon from the rear, bidding him at the same time to bring up peltasts to the front. That Xenophon hesitated to do, for Tissaphernes and his whole army were coming up and were well within sight. Galloping up to the front himself, he asked: "Why do you summon me?" The other answered him: "The reason is plain; look yonder; this crest which overhangs our descent has been occupied.[55]

Jewish historian, Josephus in his The Wars of the Jews also used an illeist convention when he writes,

And now the Romans searched for Josephus, both out of the hatred they bore him, and because their general was very desirous to have him taken; for he reckoned that if he were once taken, the greatest part of the war would be over. They then searched among the dead, and looked into the most concealed recesses of the city [56]

Matter of fact, the Illeism in Julius Caesar’s commentaries of the Gallic wars is complete, in that throughout the work, he refers to himself in a third person narrative. There are also no grounds to infer anonymity from this basis.

CASE 2: Argument From Medical Language

Luke, possibly the only gentile among the gospel authors, acquired the traditions of Greek historical writing in antiquity. [56] His treatise, Luke-Acts, is the most voluminous in all of new testament books and contains such intriguing accuracy, the author has been placed among the ranks of historians of his time. While the author of Luke-Acts might have proven himself a capable historian, how is this exactly supposed to help us identify him with Luke the physician?

In his well-known An Introduction to the New Testament and the Origins of Christianity, Delbert Burkett takes quite a skeptical approach to the New Testament documents. On the authorship of Luke-Acts, for example, he argues that,

“Since Luke-Acts nowhere exactly identifies its author, we are dependent on internal evidence from literature itself and on church tradition for clues to his identity.”[57]

He then concludes that

“Nothing in Luke-Acts, however, indicates author had any specialized knowledge in medicine.”[58]

in truth, nothing seems to suggest that Luke is the author, even though Luke's preface was addressed to a certain Theophilus, his name isn't inscribed on the preface....except that we come to a radically different conclusion when one reads Luke-Acts in Greek.

This is exactly what William kirk Hobart did, all the way back in 1882. In his highly informative The Medical Language of St.Luke, Hobart was able to demonstrate, in fact, that the writer of Luke-Acts was a physician. Employing medical sources by Hippocrates, Dioscrides and Galen, he was able to scrupulously affirm the medical phraseologies' employed by the writer of Luke-Acts shows that the said writer was very well acquainted with diseases and other medical conditions. In essence, Hobart's overview of Luke-acts is not only replete with medical phraseology which were commonly used in Greek medical schools, but a lot of these terms are Hapax Legomena, a term that occurs only once in a corpus; in other words, these words are not just only exclusive to Luke-Acts out of the whole New Testament, but they occur just once in the treatise, portraying the author's impressive vocabulary power in medicine.[59]

There are three main physicians being compared with the Author of Luke-Acts. Hippocrates (460-370 B.C) recognized as the “father of medicine” was the most prominent Greek physician. Galen of Pergamos, was a Roman physician, philosopher and surgeon. He specialized in physiology, pharmacology and pathology. Finally, there's Dioscorides, a contemporary of Luke andone of the the chief authorities on medicine and pharmacy in antiquity. His work is so important it has been translated into Latin, Arabic and Armenian.[60] Save for Hippocrates, all extant Greek medical writers were Asiatic Greeks very much like Luke was.[61]

The first observation i would like to point out is the image below, where a side-by-side comparison between Luke's epistolary introduction and Dioscrides preface for his De Materia Medica, reveals the same order of presentation, which probably implies the literary idiosyncrasies of antiquarian physicians.

This comparison is made even more plausible when skeptical Historian Gerd Lüdemann, speaking about Luke’s preface, notes that this,

Hereby, shows his knowledge of Ancient Greek historiography, that’s the way a historian would write his work.” [61]

Secondly, Luke’s gospel is replete with medical terms, many of them Hapax Legomena. He uses them to medically describe sicknesses or healings while the other gospel writers simply used plain language. here are a few examples of the several Hapax used by Luke which can be found in other Medical works. A few random examples,

• Acts 28:3 “fastened on/kathēpsen/καθῆψεν” (used by Dioscrides in referring to poisonous material introduced into the body, which tells us Paul was infact bitten, as opposed to having the viper coiled around his hands. This is why the island’s inhabitants expected Paul to succumb to the effect of the venom)

• Luke 9:39 “foameth/aphrou/ἀφροῦ” (a hapax used by Hippocrates and Aretaeus as a symptom of epilepsy)

• Luke 1:1 “a declaration/diēgēsin/διήγησιν” (a hapax used by Hippocrates)

• Luke 1:36 “ old age/gērei/γήρει” (a Hapax used by Galen for the last of three stages in human development)

• Acts 15:39 “contention was so sharp/paroxysmos/παροξυσμός” (A hapax used by Hippocrates and Galen in referring to paroxysmal attacks or sharp pain)

• Luke 5:18 “taken with palsy” (used by both Hippocrates and Galen)

• Luke 5:2 "were washing/eplynon/ἔπλυνον” ( hapax denoted by Hippocrates for cleansing wounds)

• Acts 26:24 “mad/Mainē/Μαίνῃ” (Hippocrates uses this hapax in his treatise on mania)

• Acts 7:20 “Nourished up” (used by Hippocrates )[62]

Halbert doesn't end here; he makes an interesting inference that even though Luke's use of medical phraseology, and textual analysis of the treatise portrays an experienced physician wrote the treatise, one can reasonably contribute a stronger basis for Luke being the author and include because I find it to be defensible.

He starts by arguing for the plausibility that Paul, while embarking on his missionary travels to the gentile lands, was in a delicate state of health or some form of infirmity, and having evaluated it to examine its tenability, i think i find the argument plausible was well.

There are generally 3 sections in the Luke-Acts treatise where the author transits from a third-person narrative to a first-person narrative, as if the writer were present in the events being described (Acts 16: 10-17, Acts 20:5-21, Acts 27:1-28). Think of this short narration for example,

It was a warm Saturday morning and after his usual hypnic jerks, John Squirmed mildly to the left side of his bed with a grunt, "i wish this would just stop." he complained. Mustering his will power, he opened his heavy eyelid to the thin blades of sunlight shining through narrow openings of the curtain, unto the dark grey carpet. After some indulging the urge to continue laying for a few minutes John eventually up, showered, and poured himself some cereal before heading out to Victoria's place. On his drive there, the thought of Sam's warning from the previous night, to sleep early kept punctuating his mind. perhaps if he stopped gaming for hours into the midnight, the hypnic jerks might abate. After meeting Victoria, we left to the movies, met up with our co-workers for the picnic. At 6:15 PM, John announced his departure, it was time he took Sam's advice. After taking a swig of water, he walked into his room and splattered himself on the bed; he was fast asleep in minutes.

At the beginning of the narration, it was being read from a Third-person narrative until there's sudden switch to "we left to the movies." The speculation would be that John and the narrator met at Victoria's house and parted at the picnic where the narrator switches back to third-person.

Halbert begins his analysis in Acts16:6-8 of the we-sections where Luke recounts Paul's missionary movement, it is seen that Paul abode for a little while in Galatia and preached the gospel to them.[63]

“They went through the region of Phrygia and Galatia....”

- Acts 16:6 NET

In Galatians 4:14, before Paul recounts how the Galatian church first received him, he writes,

"but you know it was because of a physical illness i first proclaimed the gospel to you"

suffering from this illness, Paul likely communicated to Luke for medical attention at Troas (where the writer switches to first-person narrative) and was needed no further than Philippi. He also speculates that Luke was likely converted during that period. [64] The next piece of clue that may help establish the writer's authorship would be Acts 27:3,

"And the next day, we touched at Sidon and Julius courteously entreated Paul, and gave him liberty to go to his friends to refresh himself."

There two observations to be made here. Firstly, that writer uses the term “Courteously” (philanthrōpōs/φιλανθρώπως) which further affirms the medical context with which writer was documenting these events. This is because physicians in antiquity were always inculcated to adopt kindness, courteousness and empathy in their conduct with patients. Hippocrates, for instance, expressed that dignity, kindness and philanthropy (philanthrōpōs/φιλανθρώπως) should characterize one’s medical profession. Even Galen calls the medical profession a philanthropic (philanthrōpōs/φιλανθρώπως) endeavor. [64] Secondly “To refresh himself” (ἐπιμελείας τυχεῖν) which connotes recuperating from an illness or infirmity and this seems feasible because Luke uses the same medical term “And took care” (καὶ ἐπεμελήθη) in Luke 10:21 referring to the robbed traveler in the parable of the good Samaritan when he was left in the inn to recover. [65]

The last critical pointer to establish Luke's authorship in this line of inquiry would be the book of Colossians. The epistle to the church at Colossae was written ca. A.D 60-62, the time which Paul made his voyage to Rome and would later be imprisoned for two years. From prequel assertions, we can infer strongly that Paul was in a delicate state of health and a voyage to Rome might further precipitate his condition, hence the need to have Luke accompany him. In Paul's closing remarks in col 4:14, we read,

"Our dear friend Luke the physician and Demas greet you"

-Col 4:14 NET

If Paul was writing from Rome and Luke was with him, the obvious conclusion is that he accompanied him in the sea voyage hence why we find the last we-section, (Acts 27:1-28) written in a first-person narrative.

Fortunately, there scholarly works that corroborate this. Sir William Ramsay, an archeological expert of Asia Minor was first an adherent of the Tübingen Theory, which argues that Luke-Acts was a late 2nd century production. However, he would go to change his stance when he noticed the accuracy with which the author describes Asia Minor and the Greek east, in consonance with the period which writer alludes, as if he had witnessed these event he were narrating. [66]

James smith of Jordanhill, an experienced yachtsman who was familiar with the Mediterranean Sea over which Paul sailed, also testifies of Luke’s impressive precision in his work The voyage and shipwreck of Paul (1848). Smith demonstrates how by Luke’s account of the several stages of the voyage he was able he to find the likely location of the shipwreck [67] it becomes discernibly evident that the writer of Luke-Acts, as Paul’s companion, partook in these events and as such was able to reliably reenact them in the texts. it is needless to say there's no way a Greek author in a different land writing Luke-acts could have replicated this, seeing as he would have to be present himself and be known by Paul.

it's also worthy of note that it seems most inconceivable that having addressed the treatise of Luke-Acts to Theophilus, there wouldn't be some sort of accompanying identification with the treatise; if not, how else was theophilus supposed to know who wrote it? as Richard Baukham has noted a few times, even if there weren't superscriptions attached to the gospels, traditions about the Gospel's authors must have been related to the churches that received these gospels, if not there would have arisen the diversity of attribution.

CASE 3: The High Plausibility of Names

Gerd thessien alludes tacitly to this when he opines that it seems natural to think that the oldest gospel was written in a land where Hellenistic Christianity originated, especially since that form of Christianity was the home of the gospels written in Greek; earlier on, it was noted how Ehrman claimed the chain of transmission of the oral tradition that make up the gospels has undergone such radical change that it would be impossible to determine, with a reasonable amount of certainty, the original contents and real authors of the gospels. In this particular case, I’ll focus more on the content because it’s actually what would predispose the inquirer to ascertain whether this was the product of original eyewitnesses or distorted oral tradition.

If it happens to be the former, it raises the bar for the gospels to be connected to their Authors. To argue this point, i'm going to be using a criteria set by a prominent new testament scholar……Bart Ehrman.

He writes,

Since Jesus was a Jew who lived in first century Palestine, any tradition about him has to fit his own historical context to be plausible.[68]

Agreebly so, as any Historian seeking derive to the originality of the texts would pretty much agree with Ehrman.

In 2002, Tal Ilan, Jewish historian and lexicographer, published her scrupulously researched Lexicography of Jewish Names in the Late Antiquity which catalogued and arranged Jewish Palestinian names from lands where Greek and Latin was spoken.

She did this by analyzing literary, epigraphic and documentary Jewish sources and with certain criteria, determines Jewish names that were statistically valid or invalid. Invalid names were ones that were fictitious, non-Jewish, non-Palestinian Jewish, Samaritan, nickname and a proselyte name.[69] Richard Bauckham, adopts this method and adopts it to the New Testament as well. The idea is, since the time period of the gospels is first century Palestine, a comparative analysis with the catalogues should yield a perfect correlation between the names of the gospels. In other words, if the gospels which were fluid as a result of a 5th-hand or even 19th hand hearsay, were possibly written by “Greek authors living outside Palestine” we ought to see a noticeable amount divergence from the names in the catalogue being carried out nearly 2000 years later, something the authors could never possibly have preempted.

Comparing gospel names with Ilan’s catalogue, shows intriguing finds; Not only does the catalogue exactly mirror the Palestinian Jewish names in the canonical gospels and Acts, we also see an agreement of name popularity in the gospels and the Palestinian Jewish names in the catalogue. This is nice, but what does this have to with anything?

Allow me clarify; In our societies, whether modern or ancient, there are certain underlying sociological undertones that contribute to naming people at the time of their birth and if those factors persist, those names are continually given. In Kenya, for instance, The Luos are known for adopting famous names for their children. A significant number of mothers named their male children Obama in 2008 after Barack Obama, whose father is Luo, was elected US president. prior to 2008, one could discern that almost no child was named Obama, as most would not have been familiar with Barack Obama prior to the historic 2008 elections.[70]

Another illustration would come from a 2016 study which shows the correlation between the exponential rise of a name and a popular song. The study shows how from 1965, the name Michelle was one of the top 20 names in America. Coincidentally, the Beatles had released Rubber Soul, an album in the same year and one of the song would go on to win the Grammy award song of the year; the name of the song is "Michelle."[71] The same is also inferred for the name "Brandy;" a song of the same name released in 1972 by looking glass. in 1967, the name ranked 804 out 1000 top names, but after brandy hit the billboard 100 list, it shot from 804 to 140! the name would eventually reach its peak position at 37 in 1978.[72]

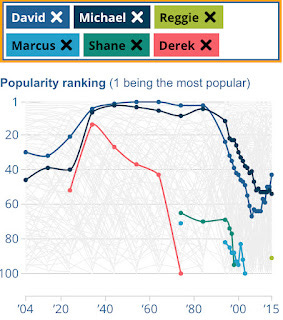

What this shows is that certain sociological trends affect the popularity of names and If another trend arises that necessitates different names, the previous names begin to decline in popularity and other sets take its place. To verify how trends can affect the popularity if names, i assessed the popularity of 6 random names from 1904-2015 into the website of the Office for National Statistics, UK and the diagram below seems to confirms that trend

From the chart, Michael and David are obviously the most popular names and rose to be top 10 in the late 1930's and remained so till they began to experience a plummet in the late 1980's. Derek rose sharply from its rank 50-something in the early 1920's to top 20 in the late 1930's.

Now back to first century Palestine, even though there's a minor variation from Bauckham and Ilan's catalogue, the top 6 high-ranking names in Palestine were,

Bauckham Ilan

(1) Simon (1) Simon

(2) Joseph (2) Joseph

(3) Eliezer (3) Judah

(4) Judah (4) Eliezer

(5) Yohanan (John) (5) Yohanan

(6) Yehoshua(Jesus) (6) Yehoshua

Bauckham echoes Ilan's thoughts that the reason why these names got popular is because they to the hasmonean dynasty (Simon Matthias and his sons), the one preceding the Herodian dynasty. The Hasmonean dynasty arose after the Maccabean revolt (167-141 B.C), which toppled the oppression of the Seleucid Empire.

Thus it was considered patriotic to name children after these names. Also, Bauckham opines that apart from the fact that these names belonged to the Hasmonean dynasty, they were popular because they were theophoric, that is, incorporating "YHWH" into names e.g.,Yehoshua/Yeshua(johsua/jesus), Yehudah(Judah) and Yohanan (John)[73].

Unlike Kenya or the United States, this was the past where population density was lower and even more so in first century Jewish Palestine. Bauckham notes that since about 12 popular names were being shared within half the population of Jewish Palestine, it became a matter of necessity to distinguish one person from another.[74]

To do this, disambiguators were used and they were quite effective in telling people with high ranking names apart. Patronymics, places of origin, and profession were employed as disambiguators. This is why the result of comparing the gospel names with catalogues is significant, because the setting of the gospels is in 1st century Palestine and they happen to reflect the exact pattern of names in that period'; in essence, this explains why people were referred to as Jesus "of Nazareth" or Simon "of Cyrene" or Simon "the Tanner" given that these were high-ranking names for which disambiguators had to be used.

Aforementioned is that Ilan catalogued non-Palestinian Jewish names, some of which include Ptolemaius, Positheus, Sabbataius, Pappus, e.t.c yet, we do not find as much as find these names in the gospels, rather they remarkably reflect the name trends of first century Jewish Palestine, despite being a smaller data sample when compared with Jewish sources.

if the gospels traditions are decontextualized from its true origins, as Ehrman posits, the comparison with the catalogue should expose this but this isn't what we find. if anything, this tells us the gospels portray a highly reliable eyewitness account given the impressive detail and intention in disambiguating these characters.

In simple words if one studies Ilan’s Catalogue and goes on to read the gospel, one ought to notice that disambiguators being used used for only popular/high-ranking names and not for names that weren’t common. Incidentally that is exactly what one sees in the gospels. For instance the names of the disciples in Matthew 10:2-4 demonstrates this.

-Let HRN = High ranking name

-Let LRN = Low ranking name

- Let (N) = position of name popularity in Palestine.

•Simon “called Peter”: HRN (N=1)

•Andrew: LRN, no disambiguator.

•James and John “sons of Zebedee”: HRN (N=11, 5).

• Thomas: LRN, no disambiguator.

•Matthew “the tax collector”: HRN, (N=9).

•James “Son of Alphaeus”: HRN, (N=11).

• Thaddeus: LRN, no disambiguator.

• Simon “the canaanean”: HRN, (N=1)

• Judas “Iscariot”: HRN, (N=4)

Consequently, one would expect eyewitness who were from the land and were involved in his itinerant ministry possess some level of geographical familiarity, ranging from topography of the land to plants confined to that location. British New Testament scholar, Peter Williams analyzes this factor in the canonical gospels, in comparison with other apocryphal gospels that claim to be eyewitness accounts.

The results are quite interesting; the Gospel of Philip mentions 2 towns, the Gospel of Peter mentions just 1, while other gospels mention….none. In stark contrast, the canonical gospels uniformly mention about 23 town names [75] Moreover, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John uniformly mention 5 towns every 1000 words while the gospels of Philip, Judas, Thomas and Mary have almost no mention of place names per 1000 words [76]

Using Ehrman's criteria, we see that the gospel traditions do preserve the names of Palestinian Jews in the Gospels and it checks out with the trend of names within that particular period. We also see the disciples mentioning more town names, as if recollecting eyewitness accounts of these events, which informs any critical thinking person that these aren't 5th hand or 19th hand oral tradition but of both rich oral tradition and oral history from eyewitnesses. The apocryphal gospels perform very poorly in fulfilling this criteria. This gives veracity to the attestations of early church figures who linked the gospels to their canonical authors.

CONCLUSION

I’ve been able to show that if copies of the John, the latest gospel has started circulating in the early 100’s then the original manuscript would have been composed much earlier, probably in the end of the 1st century A.D, which places the earlier gospels at a time when the witnesses of the gospel events were alive. This would have provided means of gathering eyewitness testimony of people who had miracles performed on them by Jesus (I recommend reading Richard Bauckham’s Jesus and the eyewitnesses for more on eyewitness testimony ) I also explored this regard for the fringe audience that posit the gospels as written after 100 A.D.

Drawing from New Testament scholarship and classical works, I ascertain that the gospels were written like Greco-Roman biographies as such, adapted some of its literary features, one of which includes anonymity. Through this, I draw a distinction between Partial anonymity and Absolute anonymity to support my foci: while partial anonymity is indisputable given the absence of names, to infer Absolute anonymity based on this premise is unfounded because classical works (including biographies) circulated as partially anonymous works because the audience apparently knew the authors though the gospels weren’t superscripted.

I posited an argument from language infixed in the Lukan Corpus, which demonstrates that the internal evidence of medical phraseology, and its parallel with works of Greco-Roman medical writers, strongly establishes that an experienced physician wrote the treatise of Luke-Acts. Secondly, the use of medical language in the “we-sections” vis-a-vis Paul’s tacit admissions in his epistles, suggests strongly that Paul was Ill during his missionary journeys, creating a basis for Luke’s help as a physician, thus, his participation in the events that he reports.

The evidence that the gospels were written by their attributed authors outstrips, if not invalidates, claims to the contrary. It is worthy of note that most these claims proposed on non-evidenced assumptions. Unless there’s new opposing evidence, suspect of Absolute anonymity is simply synonymous to increasing our “Skeptometers” to Radical skepticism.

As I have been able to argue, the Anonymity thesis mischaracterizes the origin of the gospels into an obscure byproduct of a 2nd century-religious-conspiracy. Whether this is as a result of willful obliviousness or research lacuna, I’ll leave that for the reader to decide. Once we compare the gospels with other works of antiquity and further analyze the texts, we see critical markers that not only appreciate its literary, textual and historical worth but also its originality as eyewitness accounts and we can be once again, assured that the 2nd century testimonies of Papias, Polycarp, Irenaeus, Clement, Tertullian, The Muratorian fragment etc., holds true. In a sense, the gospels were anonymous in that the inscriptions were included in the earlier manuscripts which is what I would term partial anonymity. But we have excellent reasons to think that early Christians were aware of the Gospel’s authors even before their ascriptions to the manuscripts as “The gospel according to…”

Beyond skepticism, there’s no good reason to attach absolute anonymity to the canonical gospels; and as Martin Hengel popularly challenges,

let those who deny the originality of the gospel superscriptions in order to preserve their ‘good’ critical conscience, give a better explanation…such an explanation has yet to be given….”[77]

References

[1] Lee Strobel, The Case For Christ. p.23

[2] Peter Stulmacher. The Gospel and the Gospels. (Michigan: Wm. B.Eerdman's publishing, 1991). pp.26-27

[3] Bart D. Ehrman. Forged: Writing in the Name of God-Why the Bible's Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are. (HarperCollins, 2011). p.228

[4] Denova, Rebecca. "The Gospels" World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 26 Feb 2021.

[5] History Channel. “The Bible.” https://www.history.com/.amp/topics/religion/bible#the-gospels

[6] Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus: the apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium. (Oxford University Press, 1999). pp.45-6

[7] Bart D. Ehrman, Lost Christianities: The battle for scripture and the faith we never knew. (Oxford University press, 2003). p.235

[8] Ehrman, Jesus: the apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium. p.109

[9] Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus, Interrupted: revealing the hidden contradictions in the bible (and why we don't know about them). (HarperOne, 2010). p.149

[10] ibid, p.147

[11] Ehrman, Jesus: the apocalyptic prophet of the new millennium. p.53

[12] ibid, p.42

[13] MythVison Podcast, Everything you knew about the gospels is wrong. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PLKMcIz8Vd0&t=1272s

[14] ibid

[15] Doston Jones. “When we’re the gospels written and how can we know.” https://bibleoutsidethebox.blog/2017/07/24/when-were-the-gospels-written-and-how-can-we-know/

[16] Timothy Paul Jones, Conspiracies and the Cross. (Florida; Frontline, 2008)

[17] Justin Matyr. Dialogue with Trypho. Chapter CIII.

[17] Norman Geisler, Christian Apologetics. (Baker Publishing, 2013)

[18]

[19] Timothy Paul Jones, Conspiracies and the Cross.

[20]

[21] Adolf Deissman. The Papyrus fragment of the fourth gospel. (The British weekly, Dec 12,1935) https://variantreadings.files.wordpress.com/2019/05/deissmann-p52-english.pdf

[22] Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History. (4.3)

[23] ibid

[24] Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History. (3.39)

[25] Clyde Votaw Weber, The gospels and contemporary biographies in the greco-roman world. (Fortress Press, 1920). p.2

[26] Victoria Emma Pagan. Conspiracy Narratives in Roman History. (University of Texas press). p.94

[27] Irenaeus. Against heresies. (3.1.1)

[28] Eusebius. Ecclesiastical History. (5.20.4-8)

[29] (Luke 3:12-13, Matthew 17:24-26, Luke 15:1-2, Matthew 5:46, Mark 2:15)

[30]Martin Hengel. The four gospels and the one gospel of Jesus Christ. (Trinity press international, 2000)

[31] ibid

[32] Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History. (29.3:3)

[33] Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History. (30.6:35)

[34] (Luke 5:29)

[35]Richard Burridge. What Are The Gospels? a comparison with Greco-Roman biography. (Wm. B.Eerdman's publishing, 2004)

[36] Samuel Byskorg. Story as History - History as Story: The gospel Tradition in the Context of Ancient Oral History.

[37] Richard Burridge. What Are The Gospels? a comparison with Greco-Roman biography. Wm. B.Eerdman's publishing (2004)

[38] Mike Licona. Why Are There Differences in the Gospels: What we can learn from Ancient Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017)

[39]Craig Keener. Christobiography: Memory, History and the reliability of the Gospels. (Wm. B.Eerdman's publishing, 2019)

[40] Friedrich Blass. Philology of the Gospels. (Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2005)

[41]Richard Burridge. What Are The Gospels? a comparison with Greco-Roman biography. Wm. B.Eerdman's publishing (2004). p.60

[42] Charles Horton. The Earliest Gospel: the origin and transmission of the earliest gospels. (London and New york: T&T Clark international). p.7

[43]Clyde Votaw Weber, The gospels and contemporary biographies in the greco-roman world. (Fortress Press, 1920). pp.10-11

[44] Charles Horton. The Earliest Gospel. p.8

[45] Doston Jones, Yes, the four gospels were originally anonymous: Part 1(2017) https://bittersweetend.wordpress.com/2012/04/15/third-person-gospels/

[46] ibid

[47]Simon Gathercole. "Alleged Anonymity of the Canonical Gospels." The journal of theological studies,Volume 69,issue 2 ( 2018)

[48] Simon Gathercole. "Alleged Anonymity of the Canonical Gospels." p.7

[49]Simon Gathercole. "Alleged Anonymity of the Canonical Gospels." pp.7-8

[50] Simon Gathercole Alleged Anonymity of the Canonical Gospels."pp.8-9

[51]Bart Ehrman. Forged. p.220

[52] ibid

[52] Simon Gathercole. "Alleged Anonymity of the Canonical Gospels." p.9

[53] Bart Ehrman. Lost Christianities (New York: Oxford University press, 2003).

[54] Doston Jones, Yes, the four gospels were originally anonymous: Part 1(2017) https://bittersweetend.wordpress.com/2012/04/15/third-person-gospels/

[55] Xenophon, Anabasis. Translated by G.H Dakyns (3.4.9) https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1170/1170-h/1170-h.htm#link2H_4_0021

[56] Flavius Josephus, Wars of the Jews. Translated by William Whiston (3.8.1) https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2850/2850-h/2850-h.htm#link32HCH0008

[57] Delbert Burkett. An introduction to the New Testament and Christian origins.(Cambridge university press) 2019. p.195

[58] ibid. p.196

[59] Willliam K. Hobart, The Medical language of St.Luke. (Dublin University Press, 1882)

[60]John M. Riddle, Dioscrides on pharmacy and medicine. (Austin; University of Texas Press, 1985)

[61] F.F Bruce, The New Testament Documents: Are They Reliable?. p.96

[62]Willliam K. Hobart, The Medical language of St.Luke

[63]Willliam K. Hobart, The Medical language of St.Luke. p.293

[64] Willliam K. Hobart, The Medical language of St.Luke. p.296

[65] Willliam K. Hobart, The Medical language of St.Luke. p.297

[66] ]F.F Bruce, The New Testament Documents. p.107

[67]F.F Bruce, The New Testament Documents. p.106

[68] Bart D. Ehrman, Jesus, Interrupted. pp.154-5

[69] see Tal Ilan. Lexicon of Jewish Names in the Late Antiquity: Palestine 330BCE - 200 CE (Texts & Studies in Ancient Judaism, 91, 2002)

[70]BBC News, Africa's Naming Traditions: nine ways to name your child. (2016). https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-37912748

[71] Napierski-Pranci, Michelle. "Brandy, You're a fine name: Popular music and the naming of infant girls from 1965-1985." Studies in Popular culture, Vol. 38, no.2, 2016, pp 41-53

[72] ibid

[73] Richard Bauckham. Jesus and the eyewitnesses.

[74] ibid

[75] Peter Williams. "New Evidence for the Gospels." Lecture at Lanier theological library

[76] ibid

[77]Martin Hengel. The four gospels and the one gospel of Jesus Christ. (Trinity press international, 2000)